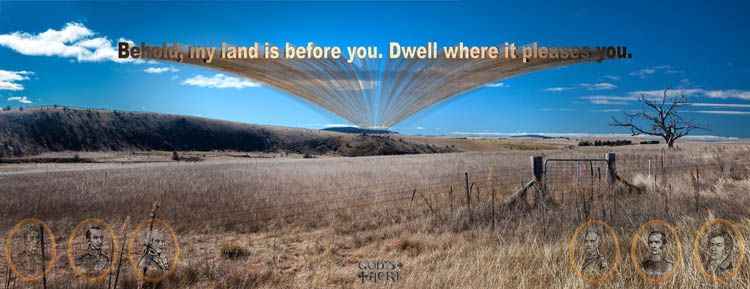

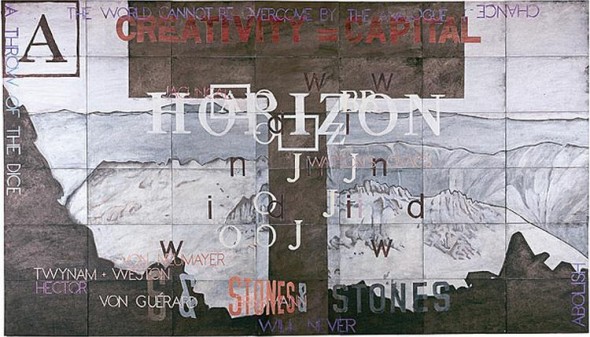

The base photograph for this image was recorded along the now-overgrown Farm Ridge Fire Trail, at the top of a climb up from the Tumut River and several kilometres north of the ruins of the Farm Ridge Hut. It looks south along the ridge towards Mt Jagungal and the Main Range in the far distance.

In this image I wanted to allude to the same issue taken up in another image (Doubtful) – the contested nature of place names in the Snowy Mountains region, and the conflicting narratives which lie underneath the various names in competition.

The Aboriginal visitors to this area (which appears to have never had permanent residents) used different names to denote a place, according to their language group, clan membership, level of initiation into sacred knowledge – and even the season. ‘Jagungal’, the name now applied to the largest mountain of the area, is only one of the names transcribed by early European visitors, who also recorded the name as ‘Targil’, ‘Teangal’, ‘Jar-gan-gil’, ‘Corunal’ and ‘Coruncal’. It is no longer possible to know whether the name ‘Jagungal’ would have been understood by the original inhabitants.

It is certain, however, that ‘Bogong’ was widely used to indicate the places where Bogong Moths could be found during the summer months, the high country places with granite boulders that were destinations for seasonal migration and feasting. Jagungal was referred to as “The Big Bogong”, so as to distinguish it from other destinations such as those now known as Dicky Cooper Bogong, Paddy Rush’s Bogong and Grey Mare Bogong.

The ‘Bogong’ name referred not only to the peak, but also to the surrounding region. The name identified not just a place – but the function and value of the place as well i.e. as country where Bogong Moths may be had.

The European pastoralists who commenced their own seasonal visits to the region in the second half of the 19th century demanded a more precise and detailed set of names for the topographic features and localities of the area, and set about putting their own names onto the landscape. For them, this naming of places was connected with the assertion of ownership; if I know names for all the places in a region, especially if I have myself given them names, then my claim to a legitimate and proprietorial relationship with the place is strengthened.

Like the original inhabitants, the mountain stockmen frequently adopted place names which referred to some story associated with the place (e.g. ‘Pugilistic Creek’) or to the function or value of the area. ‘Farm Ridge’, which runs north from near the foot of Mt Jagungal along the Tumut River, is a name which clearly denotes the area as a place for white Australian agriculture – and no longer as a place for feasting on the Bogong moth. (Though, interestingly, the mountain stockmen who visited and worked in this area up until about 60 years ago would still refer to Jagungal as “The Big Bogong”.

In this Farm Ridge/Bogong image, I have tried to juxtapose these two opposing visions of the mountain scene. The ‘Bogong’ name is depicted as tied more closely to the landscape (through thousands of years of use), with the ‘Farm Ridge’ name tacked on (or suspended from a tree branch) in a more fragile way, reflecting a shallower connection to the land. One interpretation could be that the country ‘knows itself’ as Bogong, but has not (yet) come to identify itself as Farm Ridge.

The interesting thing about both names however (common to many place names) is that neither name reflects the actual current human use of the land. No-one comes to harvest the summer Bogong moths any more, and summer grazing of stock in this region, now designated as the ‘Jagungal Wilderness’ within the Kosciuszko National Park, was stopped decades ago.

However the Bogong Moths still come every summer.

![allen Annie Hall [still] (1979). Woody Allen. Spoken dialogue: “Photography’s interesting, ‘cause, you know, it’s a new art form, and a set of aesthetic criteria have not emerged yet.”](http://www.jokar.com.au/blog/wp-content/uploads/allen-310x150.jpg)