Ghosts in the photographs

Ghosts in the survivor’s testimony

Ghosts in the fading street video

Sudden slides and stops in the story

The jumps jar

Genewein the model bureaucrat

Genewein the fotoamator

Genewein the Nazi piper, leading a dead dance

from the trains to the ghetto to the furnace

Lovely photos

Artful use of colour

A gentle documentary sensibility

Nicely framed,

Very carefully framed,

Unhinged

We all know what this story looks like, zoomed out and unfolded

We’ve seen the panels with the horrors, all unfolded

by other photographers, less gently

We’ve all seen the ghosts

They don’t even shock us now

Polish filmmaker Dariusz Jablonski’s Fotoamator (1998) aims to present a comprehensive ‘re-visioning’ of photographs taken by the Nazi bureaucrat Walter Genewein at the Litzmannstadt (Lodz) Ghetto in WWII. It’s darkly powerful, thoughtful, deeply moving, and masterfully made.

Photography was thriving in 1930s Germany, with the emergence of many amateur photographic clubs. The growth of popular photography exemplified the penetration of modernist thought and aesthetics into popular culture at this time, in Germany as elsewhere. Germany was also at the forefront of developments photographic technology, with the first known example of a colour negative being a depiction of German factory workers (with a swastika clearly visible in the background).

Photography had been exploited for propaganda use by all parties during the “increasingly hysterical political scene” of the Weimar Republic. The Nazi Party was closely associated with the IG Farben (now Agfa) corporation, and was well aware of the propagandising power of the still and moving image. This was perhaps best exemplified in the work of Leni Reifenstahl (e.g. Triumph of the Will 1934, produced by the Ministry of Propaganda with some 30 cameras and 120 production crew).

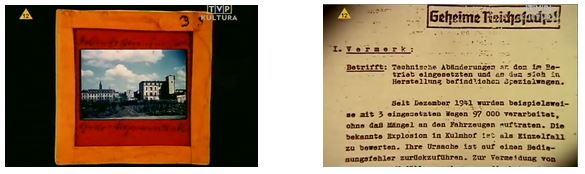

The Austrian accountant Walter Genewein was an enthusiastic amateur photographer – but was also a middle-ranking official in the Nazi bureaucracy, assigned to work in the Łódź Ghetto, and rising during the course of the war to a position as chief accountant in the (200-strong) ghetto administration. He appears to have been a highly ambitious, diligent and loyal worker. Several hundred colour slides made by Genewein during his time in Łódź were uncovered in 1987, depicting scenes of Jewish workers, street scenes, Nazi officials at work and at social occasions.

The scenes are mostly depictions of daily life in the ghetto rather than significant events, and are, in themselves, ‘unremarkable’. In many ways, and in spite of their subject material and their early use of colour transparency film, they were representative of vernacular photography of the time.

His precise motivation in making them is unclear, however it evident that he thought that his photographic activity might be used to advance his career. He was a ‘hobbyist’, interested in photography as an end in itself, and corresponded repeatedly with Agfa in an effort improve the colour accuracy of images processed in their laboratories. Also, as the time was seen as the foundation of the Third Reich, he may have felt that the photographs would contribute to the documentary record (and justification) of its establishment.

Collectively, the slides draw attention to the efficient and productive management of the ghetto, presenting “a showcase of the ghetto for the approving eyes of other Nazi officials both inside and outside the ghetto”.

In Genewein’s photographs, the subjects seem to be ‘objectified’, presented more as ethnographic specimens than as individuals. (However, unlike many Nazi photographs of Jews, there is no obvious attempt to depict them as deviant, diseased, or sub-human.) This approach is taxonomic or inventorial, resembling in this respect the earlier work of August Sander. The ‘coldness’ created by this approach is amplified because, in common with many amateur images, the scenes were typically shot through a fairly wide angle lens, creating further distance between the viewer and subject.

It is clear that Genewein (along with almost all of his contemporaries, both in Germany and elsewhere) did not question the authority of the photograph as a documentary record of reality. The power of such photography rests on the viewer’s belief that “what is seen is the result of objective recording… [of] a piece of authentic actuality”. The ‘actuality’ presented is one of order, productive work activity, and the rightful dominance of the Nazis over their inferiors.

We do not (and cannot) see the photographs as the photographer did. Our viewing of them is informed by our historical knowledge, of the atrocities that were simultaneously occurring in Łódź, just outside of the photographs’ frame, and subsequent to the images being taken. Where Genewein saw a worksite, we see “a site of decelerated mass murder”.

However the photographs’ claim to authenticity is nonetheless powerful and it can be hard to resist acceptance of the Nazi perspective that they project. In Fotoamator, Jablonski sets out to disrupt this ‘Nazi gaze’, and to release Genewein’s photographic subjects from their objectification.