This post contains some thoughts on the incorporation of text in still photography, and was written as notes for my Private Thoughts in Public Places project.

Text and images have been combined in art since writing was first used. Written text was routinely combined with visual imagery in ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Greece, and by artists from traditional Chinese calligraphers , to the creators of illuminated manuscripts in Middle Ages and Renaissance times. The text generally served to provide descriptive information or labels of the image content, or to impart messages of religious or political significance. The text generally formed an integral part of the artwork.

The incorporation of text in western art became less common in the succeeding centuries, but by the early 20th century (most notably amongst Cubist, Dadaist and Surrealist artists), text began to be employed to deliver conceptual messages, to amuse or to comment on the nature of art and the functions of language itself .

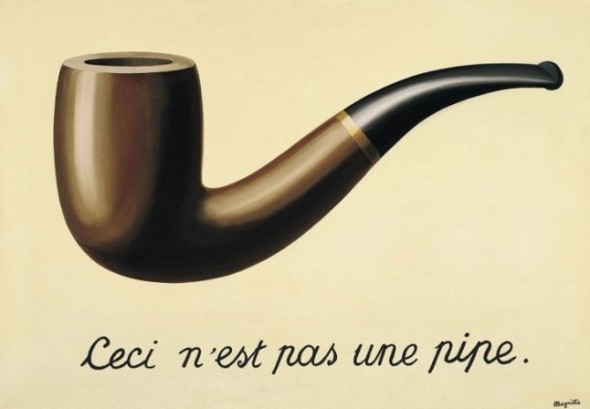

As well-known examples, René Magritte highlighted the difference between objects and their referents in The Treachery of Images (La trahison des images) (1928-29), and Marcel Duchamp played with language and visual puns in many of his works. His aim was to move from creation of art designed simply to provide visual enjoyment (which he termed ‘retinal art’) to art intended to engage and challenge the mind of the viewer, art in which the expression of ideas was paramount. Language formed a key part of that approach.

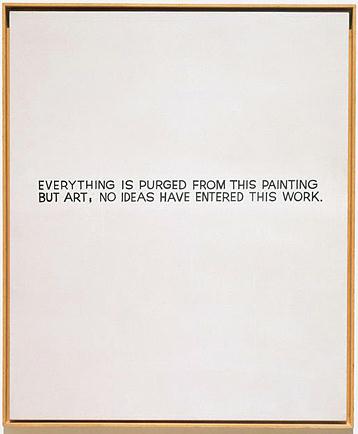

By the 1960s and early 1970s, some conceptual artists were producing work in which the use of text to deliver artistic content had entirely supplanted the visual elements of their work. This was no longer text in art, but text as art. For example John Baldessari, in his work of the late 1960s, famously sent his work out to be created by a local signwriter.

Pop art of the 1960s addressed the place of mass media in defining contemporary cultural identity, and postmodernist artists challenged the notion of the artist as author-creator. Both of these movements have made extensive use of text as a vehicle for expressing ideas about art and within artworks.

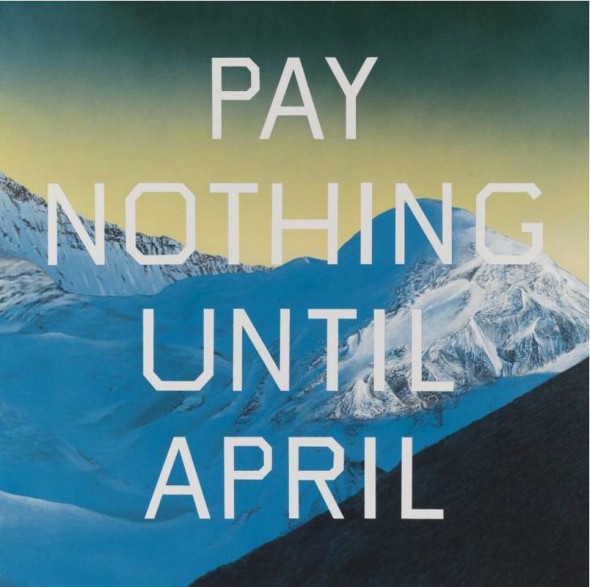

Bruce Nauman has directly used text in his photographic and sculptural work, and based many of his images on visual puns (e.g. in “Bound to fail”). Ed Ruscha created series of ‘word paintings’ containing words (and later, phrases) for ironic or satirical effect.

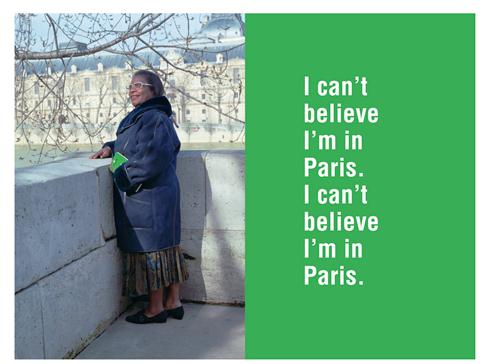

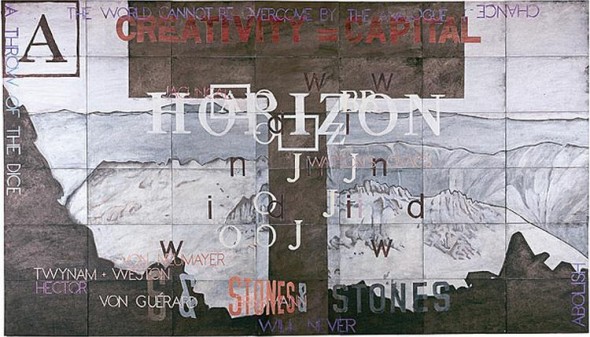

Contemporary culture is now saturated with images and text, often – or perhaps usually – in combination. The urban landscape, advertising, mass media, web content (even t-shirts!) all deliver information primarily in the form of text-plus-image packages. The incorporation of textual elements in visual art including fine art photography is now widely practiced to the point of being unremarkable. Artists as diverse as the Australian painter Imants Tillers and the Canadian photographer Ken Lum employ text as a key element within their practice – though in different ways and for quite different purposes.

In ‘theatrical’ films however the inclusion of text is (generally, and currently) less evident – apart from the standard inclusion of titles and credits to top-and-tail the work. One notable exception is the use of subtitles to provide simultaneous translation of foreign language films.

On occasion subtitles have been employed to provide an alternate text to the spoken words of the film. For example in Annie Hall (1979), Woody Allen used ‘discordant’ subtitles during a conversation between the Woody Allen character and Diane Keaton when they’re both trying to impress each other, while subtitles appear showing their true thoughts.

![allen Annie Hall [still] (1979). Woody Allen. Spoken dialogue: “Photography’s interesting, ‘cause, you know, it’s a new art form, and a set of aesthetic criteria have not emerged yet.”](http://www.jokar.com.au/blog/wp-content/uploads/allen-310x150.jpg)

Annie Hall (1979). Woody Allen. Spoken dialogue: ‘Photography’s interesting, ‘cause, you know, it’s a new art form, and a set of aesthetic criteria have not emerged yet.’

In my Private Thoughts in Public Places project I have also sought to apply subtitle text for this purpose. The projection of this text out into the landscape (onto signs, buildings and the sky) is an extension of this approach, and an attempt to show that inner thoughts actually transform the thinker’s perception and mental construction of the landscape that they occupy. Unlike subtitles, the words are not merely a layer on top of the scene; they come to form a physical part of the environment itself.