I’m still wandering through old family photographs and documents, piecing together images and information, trying to form some coherent narrative of my father’s life.

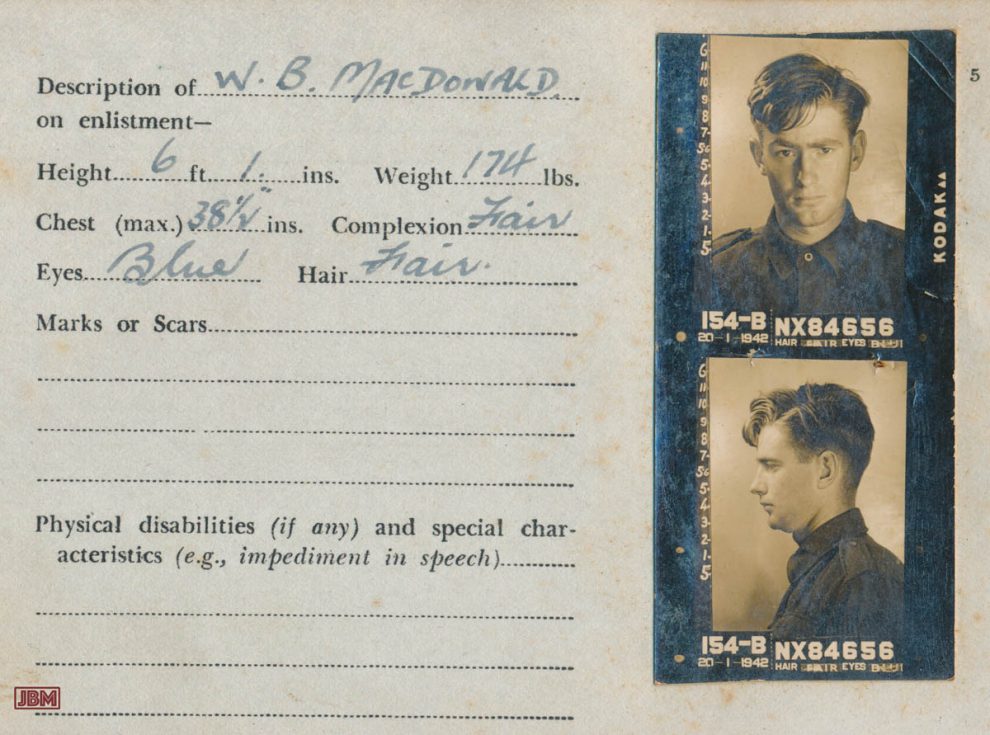

My father Bruce Macdonald enlisted in the Australian Army in January 1942. He was 19 years old, and he spent the next four years in uniform.

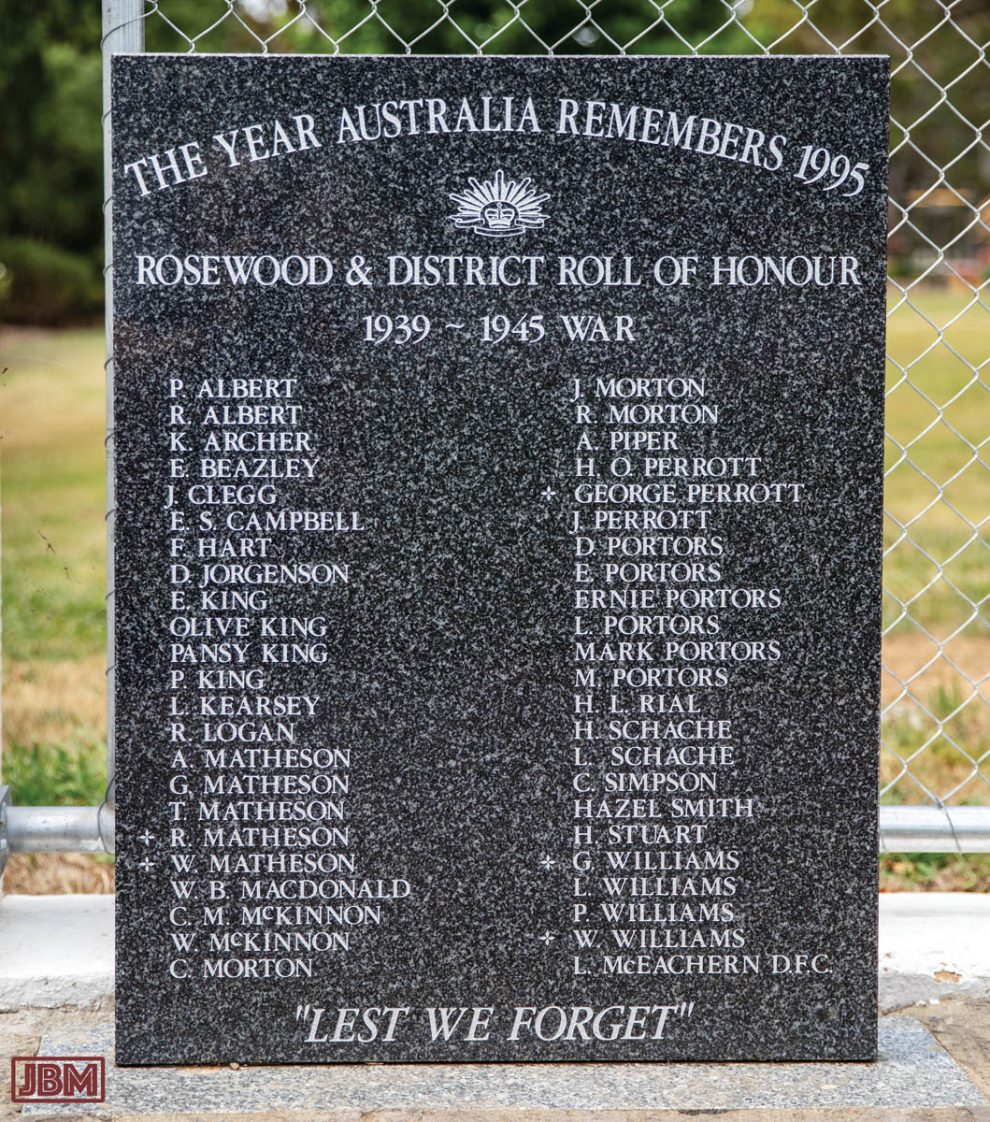

He was born and raised in Dubbo, third child of Kathleen ‘Marsie’ Samuels and Dubbo Mayor John Boyd Macdonald (after whom I was named…) Following a decline in family fortunes he left school at 14 and spent several years’ working as a jackaroo on remote properties in NSW and southern Queensland.

Nothing in his early life could have prepared him for the experience of war in the Asia-Pacific. He trained in Queensland, then saw active service in New Guinea, several islands of (what is now) Indonesia, and The Philippines, much of it on board the converted passenger ship HMAS Kanimbla.

Throughout those years of World War II he carried a photo of his sweetheart (later to become my mother) in his wallet. I like to think that her smile gave him consolation in dark times, some connection with ‘home’, and some hopes for a future after war. They exchanged frequent letters, some of which have survived, full of deeply romantic sentiment.

After the war he brought back a number of small photographic prints from places he visited along the way. I think – but can’t confirm – that he took them all himself. It’s certainly his unmistakeable handwriting on the back of each one, identifying the locations. Many are grainy and blurry, under- or over-exposed, but some of them really give a sense of what it might have been like to be there.

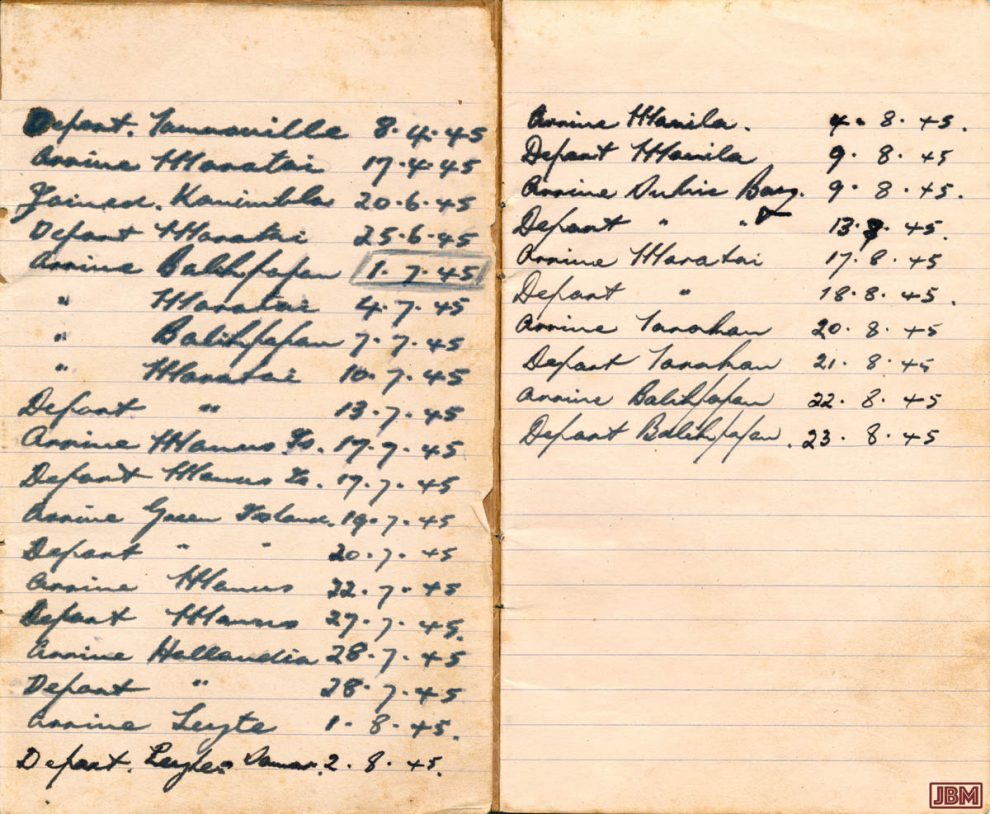

For instance, he was on board the Kanimbla on 1 July 1945, the day when Australian forces launched their largest-ever amphibious attack, on the Japanese-occupied oil city of Balikpapan. The Kanimbla was only there as a troop carrier, one of 100 vessels in the attacking force, and it left the next day after dropping off its cargo of combatants.

(He couldn’t possibly have imagined that, 71 years later, his son would be living in that same city of Balikpapan, in a house quite near to the ‘Red Beach’ where most of the Australian troops came ashore. )

Much of the city and its strategically important oil refinery was destroyed by allied bombing, naval artillery bombardment, and in the fierce fighting which ensued from 1 July. The Japanese defenders were massively outgunned and outnumbered (by about ten to one), but they put up ferocious resistance.

Consequently, the casualty figures showed a similar discrepancy. By the time hostilities ceased, 229 Australians troops had died – along with over 2,000 Japanese.

In his Army-issue notebook, my father kept a meticulous record of his movements during these latter stages of the war. Over a period of just four months he was in Townsville, Moratai (five times), Balikpapan (three times), Tarakan, Leyte, Manila, Subic Bay, and Manus Island (twice).

His service record reveals other dimensions to his service. He was hospitalised several times, due to malaria and a “bone abscess”. And he was perhaps not a model soldier, being punished on three occasions for overnight “Absence Without Leave”, and once in 1945 for “Conduct to the Prejudice of Order and Military Discipline”. For this latter offence he was fined three pounds and “awarded 14 days’ C.B.” (Confined to Barracks). Unfortunately there are no details of what had occurred…

He left Balikpapan for the final time on 23rd August 1945, and landed in Townsville on 4 September. It was a shock for me to realise that just 14 days later (on 18 September) he stood in the little church at Glenroy (near Tumbarumba), getting married to my mother.

In the photos he appears happy, sort-of shy, sort-of proud, and quite a bit thinner than the 79 kilos that he carried when he enlisted. He was probably feeling rather disoriented too, and still knocked about by the malaria and dengue that he acquired in the tropics.

Nobody talked about PTSD in those days…

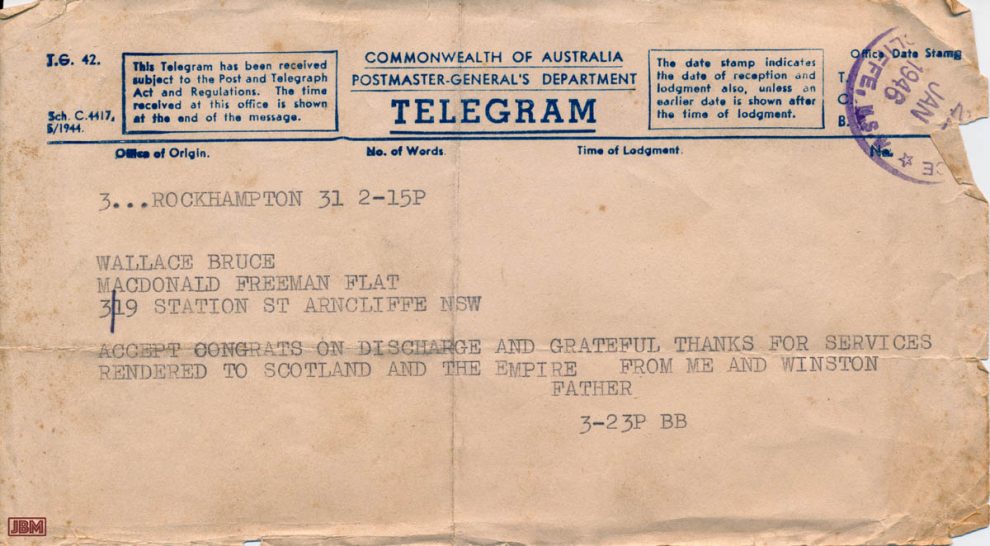

In any case he was only allowed brief leave to get married, as the Army had not quite finished with him – even though the war was over by this time. He returned to (non-combatant) service, and wasn’t ‘de-mobilised’ until 20 January 1946.

The day after he re-entered civilian life, and began the impossible task of picking up his life from where he’d left it four years previously, he received a telegram from his father, who was proud of his antipodean origins:

ACCEPT CONGRATS ON DISCHARGE AND GRATEFUL THANKS FOR SERVICES RENDERED TO SCOTLAND AND THE EMPIRE FROM ME AND WINSTON

FATHER

And perhaps also thanks from Australia…?

Postscript: in the subsequent 43 years of his life, he said almost nothing to us about his war years. And, apart from a trip to New Zealand, he never again left Australian shores. “I’ve been overseas. Didn’t like it.”