We first heard about Danau (Lake) Sembuluh and the village of Bangkal while reading the journals of the Norwegian explorer, ethnographer and naturalist Carl Lumholtz (“Through Central Borneo; an Account of Two Years’ Travel in the Land of Head-Hunters Between the Years 1913 and 1917.”). He travelled to Sembuluh almost precisely one hundred years before us. He wrote about the “attractive” lake, and wrote a little about the Dayak Tamuan people from Bangkal village.

Actually Lumholtz never quite made it up as far as Bangkal, because the water level was too low for the Dutch steamer that he was travelling in to negotiate the lake. We thought that, travelling by road, we might complete the journey for him.

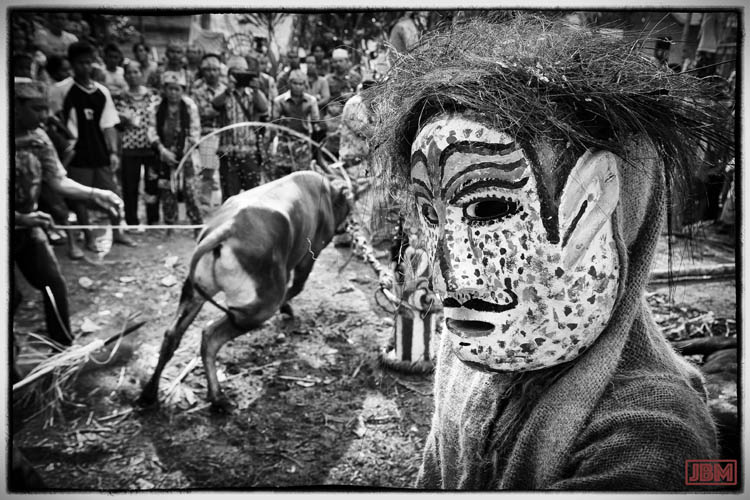

We travelled in company with our dear friend Gaye and our friend and guide Berdodi Martin Samuel (a.k.a. ‘Dodi’ or ‘Bucu’). Our main reason for the six-day trip was to attend a Tiwah ceremony (Dayak Kaharingan religion funeral), which I have written about previously (I’ve also written about some of the wonderful sapundu (funerary poles) of Bangkal village.) The Tiwah ceremonies beside Lake Sembuluh were beautiful, strange and fascinating.

But Lake Sembuluh itself, and the journey to get there, is worth a few words and pictures.

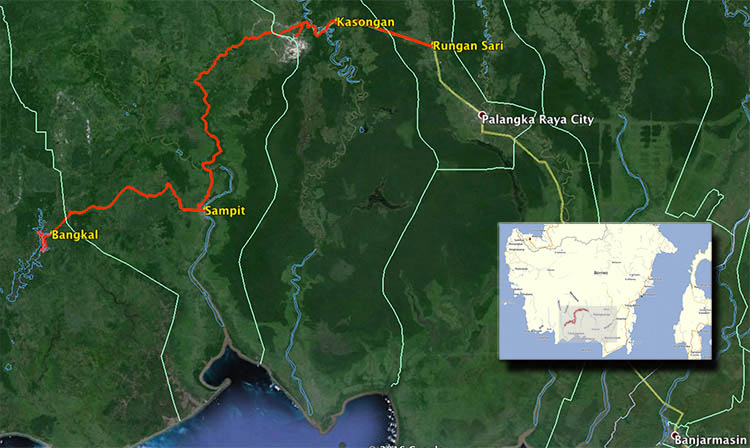

The Dayak village of Bangkal sits by the shore of Lake Sembuluh, the largest lake in Central Kalimantan. It’s about 300 km to the southwest of Rungan Sari in Sei Gohong village – which was our home at the time of our journey (back in mid-March). We’d been keen to visit the area since we first came to Kalimantan, and finally got the opportunity when we heard about the upcoming Tiwah.

Above is the GPS record of our road trip.

The five-hour drive to Bangkal stretched out somewhat with several unplanned stops along the way. Here we paused at a roadside collection of Dayak sapundu (funerary poles) and sandung (mausoleums). Karen is always keen to document such fine examples of the ‘material culture’ of the Dayak Kaharingan religion.

A little further down the road we came across a rotan (rattan) processing plant. The rotan is traditionally harvested from the forests, but with the forests rapidly disappearing, it is now more likely to be produced through small-scale plantation farming. The spiny outer layer of the rotan (which is actually a variety of palm, though it resembles a vine) is stripped off at the plantation, and then the bundles are then transported here for processing. Another outer layer is removed, and the canes are treated (twice) with sulphur, which bleaches out any colour. In this photo above the sulphur is being washed off prior to drying. It smelt like brimstone.

We were assured that the shirtless boy in the photo above had already put in a full day at school before starting work in the sulphur tank…

All the rotan from this plant is sent away for making cane furniture. Most of it goes to Java, but bundles of the best quality canes (such as those above) are exported to China.

Just a few kilometres to the southwest of the main road near Kasongan is an extensive area (maybe 50 sq km?) that has been thoroughly worked over by small-scale gold miners. You can see the result on Google Earth – it’s the big white area in the satellite image. I don’t know if any remediation was attempted afterwards, but it is now a wasteland of gravelly white sand – pits and mounds – and highly toxic (mercury-contaminated) ponds. Karen and our guide Berdodi decided against fishing or swimming there.

We stopped for a very nice lunch at Sampit – the biggest town along the road – and later walked around the newly beautified port precinct. Sampit is apparently the busiest timber port in Indonesia, and it’s also a major centre for processing of kelapa sawit (oil palm) fruit to produce Crude Palm Oil (CPO). Large numbers of yellow trucks can be seen heading to Sampit, loaded up high with the harvested oil palm fruit. We had hoped to visit one of the factories, but were unable to obtain permission (it’s difficult for foreigners…) prior to our arrival.

Outside of Kalimantan, Sampit is however best known for the kerusuhan Sampit (the ‘Sampit disturbances) of February 2001. Around 500 transmigrants from the island of Madura (and 13 Dayaks) were killed during several weeks of brutal violence, and tens of thousands of Madurese had to be evacuated from Kalimantan by Indonesian armed forces to prevent further massacres. The violence spread to other villages and cities, including Pangkalan Bun, Palangka Raya and Kuala Kapuas. It was a truly ugly episode, and one which is still fresh in the minds of the community here, since everyone over the age of 20 has memories of that time…

But fifteen years later, our biggest problem in the ‘ethnically cleansed’ town of Sampit was deciding which pineapples to buy.

We arrived in Bangkal a little before the sun set across the lake.

At the entrance to the village is a bilingual gate which spells out the values that the village aspires to – or perhaps it is a character test for visitors?

The children seemed quite pleased to meet us.

At the lakefront, a long jetty has been constructed for fishing, docking canoes, and recreational activity. We were there at the height of the wet season, and so the floor of the jetty was a little submerged.

Inundation of the jetty didn’t stop it being used. The children above are hauling a large fish trap out of the lake, from which they removed a number of (very small) fish.

Bangkal is one of the friendliest villages we have been to, and the kids – as always – were more than willing to pose for photos.

We had to wait a few days, until the Tiwah ceremonies were completed, to go out on the lake. A large number of behavioural and dietary prohibitions are enforced during the main days of the Tiwah. One of these – significant in a fishing village like Bangkal – is that you may not travel by boat.

When we did get out onto the water, we toured the northern part of the lake in a the usual klotok (canoe/longboat), with five of us sitting in a line. I got to sit up front.

A century ago, Carl Lumholtz remarked that the lake “looks attractive, though at first the forests surrounding the ladangs of the Malays are partly defaced by dead trees, purposely killed by fire in order to gain more fields.” The use of fire to clear land continues today, only on a far greater scale as the forests of Kalimantan are progressively converted to oil palm plantations.

Along most of the eastern edge of the lake, there is a thin strip of secondary forest, with the beginning of the oil palm plantations just behind. The sandy soil of the western side of the lake is not suited for cultivation of kelapa sawit, but instead is pockmarked and scarred from past gold mining, and burning to ‘clean’ the land.

So we were therefore (pleasantly) surprised to find that a moderate population of animals and birds still survive in this compromised landscape – including some large Proboscis Monkeys (Nasalis larvatus) like this one above.

At another part of the lake we were entertained by a pair of fighting (or courting?) Greater Coucal (Centropus sinensis bubutus). These impressive large (48cm) cuckoos are found across Asia from Pakistan to southern China. In Kalimantan, they are regarded by some as a pest because they like to eat the fleshy parts of ripe oil palm fruit. I would have thought that there are more than enough oil palms to share some fruit with these beautiful birds.

They are known to the Dayak people as burring bubut (because their call sounds a bit like: “but.. but… but…”), and an oil which is extracted from the wing-bones of these birds is used as a treatment for broken bones – along with massage. This treatment was even recommended to me after my motorbike accident – but I opted for surgery.

Parts of the lake were quite beautiful, even these burnt pandanus had a starkly elegant beauty when reflected in a still patch of water.

Most houses in the district are firmly constructed on dry land, but some fishermen’s homes are built on floating platforms so they can move to different parts of the lake as conditions change between wet and dry seasons.

And then we were back to the jetty at Bangkal village, leaving the tranquillity of Danau Sembuluh for the challenges of the ‘Trans-Kalimantan Highway’ and the long journey back home.