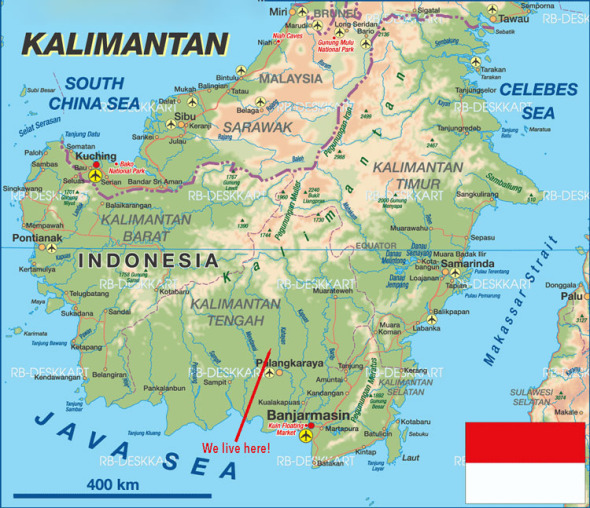

Danau (Lake) Sentarum drains into the Kapuas River, not far to the southwest of the Betung-Kerihun National Park. In the dry season there’s just a network of snaky rivers there, but now (at the end of the wet season) there’s a huge and complex system of lakes, rivers and peat swamp wetlands across the 132,000 hectares of the national park.

Despite being beautiful, with rampant biodiversity and some fascinating and friendly villages, it doesn’t get a lot of visitors. In fact we didn’t meet another tourist or see another ‘westerner’ in the more than two weeks we were in West Kalimantan.

Transport around the park, including to the several villages located within the park, is by boat – wooden barges for freight, klotok canoes with or without outboard motors for local transport and fishing, plus a few small speedboats. No cars, trucks or motorbikes. Everything happens on the water – even the cattle are kept on floating platforms in bamboo stalls, where they are hand-fed. It makes for a slow and seemingly relaxed pace of life.

A woman brings firewood to her home in the Melayu village of Semangit. We passed by very slowly, so that our wake wouldn’t swamp her canoe. But she still seemed concerned about the possibility.

The ominous-looking sky above was pictured during an abortive fishing trip, about 30 seconds before a torrential downpour arrived. We seem to have developed a talent for producing major electrical storm events when we are travelling in uncovered canoes – that’s three times so far. Within a minute it was dark and pelting down, with a weird swarm of excited little bats swooping about our heads. While our crew of three started bailing out the boat, we huddled with our cameras under our brollies, and the fishing was postponed.

There are about seven varieties of hornbill in Borneo. Big unlikely birds with enormous beak adornments (which we now know are called ‘casques’). The Rhinoceros Hornbill is aptly named, and is particularly spectacular. (Hornbill dinner party trivia: they are the only species of birds in which the top two vertebrae are fused together, so their necks can better support their big beaks.)

Hornbills are really important in traditional Dayak culture and religion, and their appearance is often seen as an omen for good or evil – depending on whether they cross your path from the left or the right side (but I can’t remember which side is the auspicious one!) We hear them frequently in the forest, but sightings are less common, and they are usually flying past at speed. So (like many birds), they are buggers to photograph.

Trees are generally more compliant. There are some large areas of mostly primary forest around the park, on islands and peninsulas. The soils are poor, but that doesn’t seem to prevent large trees, ferns, vines and fungi from growing.

675 plant species have been found so far, again including a number of unique plants. There are a number of ‘carnivorous’ pitcher plants, many of which are large and lovely and elegant. Their main prey are ants. One local delicacy is to cook and serve rice inside a large ‘pitcher’ (after removing any partially digested ants).

There’s a largish population of orang-utans in the park. In some places, such as in the forest above, you can see their nests high in just about every second tree. They make a fairly rough sleeping platform during the day out of branches and leaves. We were told that they only use each nest once, building a new one each day. Why is that? They’re not saying.

In spite of their number in the park, the wild orang-utans are very wary of humans (who can blame them?) and are notoriously difficult to observe. We spoke to one park ranger who had been working there for four years without a sighting, and to a local (middle-aged) village guy who had only come across them four times in his life.

We are frequently reminded of just how lucky we are, and so we were blessed with a sighting of a mother and baby in the forest as we were returning by canoe from an outing. Our two crew were so excited that they almost dragged us out of the boat into the swamp beside the river. A hundred metres of clambering and splashing through very difficult terrain (calf-deep mud, waist-deep pools of black water, rotting fallen logs, spiky rattan vines etc) was rewarded with a few minutes of wondrous sighting.

The mother was very protective of her baby, and soon ushered it away and started hooting and yelling at us to try and scare us off. At the time, I was more concerned about the log that had just fallen onto my head and knocked me over, and about how I was going to find my thong that had come adrift in the thick mud at the bottom of the pool I was standing in. But she certainly was a formidable sight up there!

Elsewhere in the park we encountered the large (and also endangered) Proboscis monkey. The name comes from the protuberant noses (you probably guessed) that are sported by the adult males, and which the females apparently find irresistible. And who can blame them? In Indonesia they are known as Orang belanda (“Dutch man”) which we think is rather unkind.

Almost 300 species of freshwater fish have been found in the lakes, including a couple of dozen found nowhere else (for comparison, the rivers and lakes of Europe have less than 200 fish species).

There are a number of villages either in or bordering on the park. Some are Melayu, and others (like this one above) are home to Dayak Iban people, most of whom still choose to live in longhouses. We stayed in a couple of these (such as the Meliau longhouse pictured above), and were made very welcome.

Longhouse design varies a bit between Dayak communiities, but they always have one long enclosed living room/hall/verandah/corridor running the full length, and this is where everyone gets together to meet, work, play and (sometimes) eat. Here’s Karen at Baligundi longhouse.

The man above, in the Pelaik longhouse, is repairing his fishing net. Nets and line fishing are the fish-catching methods preferred by the Iban. The Melayu people have set up hundreds (maybe thousands) of fish traps around the waterways. Between them, the poor fish don’t stand a chance.

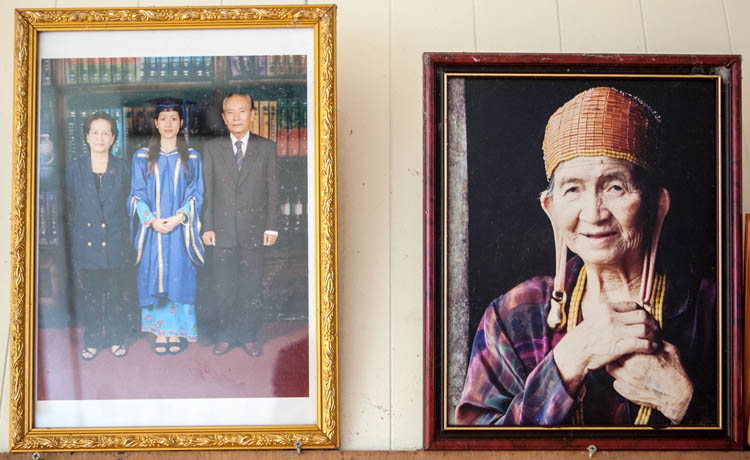

This old tattooed lady (above left), the mother of the current headman in the village of Pelaik, showed us some of the textiles that she had woven over the years. Not for sale, she was just happy to show them to us. Meanwhile the young and un-tattooed lady (above right) was in her element, asking all about weaving techniques, dye materials and the meaning of the various motifs.

In another longhouse (Baligundi), another lady was making mats from reeds, while children played around her. Karen was encouraged to have a go at the mat-weaving, after which she reported that: “it’s not as easy as it looks”.

And that probably holds true for the rest of their lives, too…