Here’s a list of “things I didn’t know about orangutans before I came to Kalimantan”. To be honest, it was pretty easy to put together a fairly long list, because I didn’t know much about them before moving into their neighbourhood. They make interesting neighbours…

Orangutans are native to the islands of Sumatra and Borneo. Since 1996 these have been regarded as two distinct species: Pongo pygmaeus in Borneo and the Sumatran species Pongo abelii. The two species may have diverged about 400,000 years ago.

Population estimates are not reliable, but there are perhaps 55,000 Bornean orangutans and only 6,000 Sumatran. That makes the Borneans ‘endangered’, and the Sumatrans ‘critically endangered’. Numbers of Bornean orangutans have halved over the past 60 years, and Sumatran orangutans are now only found in an isolated area of Aceh province. Their numbers have dropped by 80% over the last 75 years.

The main reason for population decline is loss of habitat. Peat swamp and other lowland forests continue to be rapidly cleared for oil palm plantations and forestry, but also for construction of roads and clearing of land for housing and small scale agriculture.

Orangutans share 97% of their DNA with humans. They are amongst the most intelligent of primates, having split off from the evolutionary line that led to homo sapiens about 17 million years ago, after the gibbons, and before only gorillas and chimpanzees.

Orangutans are susceptible to all of the same diseases as humans.

The subfamily of used to include other species which are now extinct. They include species that lived in Thailand, India, Vietnam and China. One of these, the Giantopithecus, was (as the name suggests) really big, in fact the largest primate ever, and it only disappeared from the fossil record about 100,000 years ago.They could be 3 metres tall and over 500kg in weight.

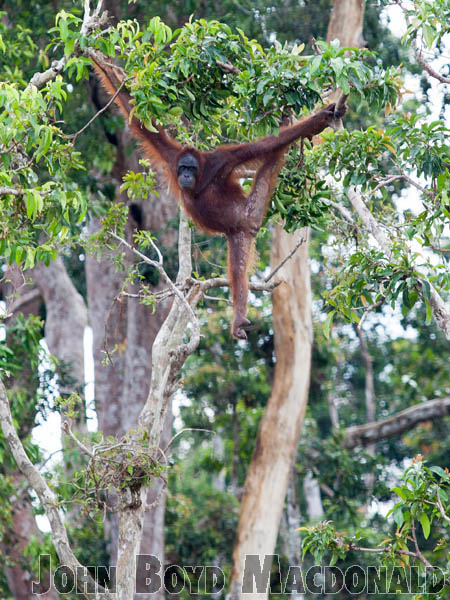

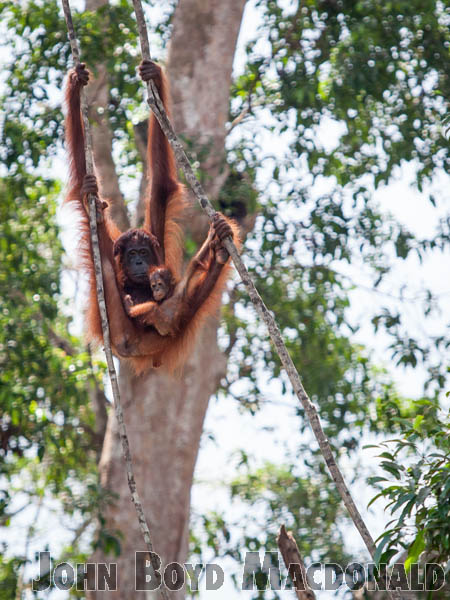

Orangutans have long toes and an opposable big toe, allowing them to grasp things (e.g. branches!) equally well with their feet as their hands.

They are almost entirely arboreal, and are the largest tree-dwelling mammal. Their long limbs and curved toes and fingers make them a little awkward when walking on the ground.

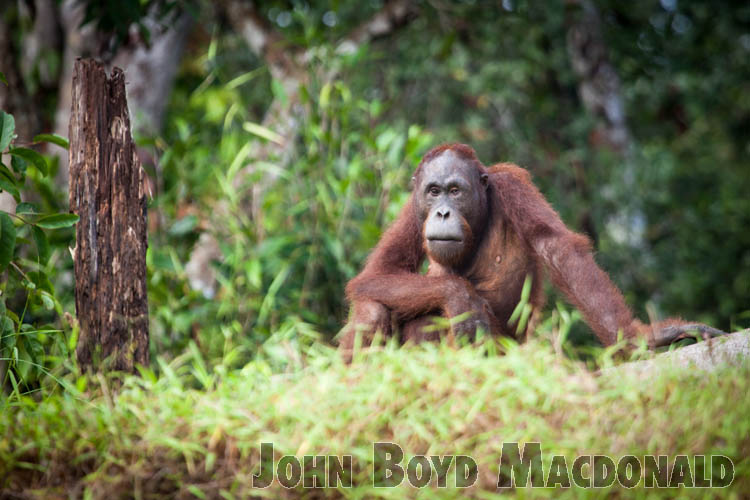

Dominant adult males grow large cheek flaps, usually by the age of 20, which no doubt the females find irresistible.

An adult male orang-utan stands about 140cm tall, weighs around 75kg or more, and and has an arm span of TWO METRES! Adult females are about half that weight, and about 20cm shorter.

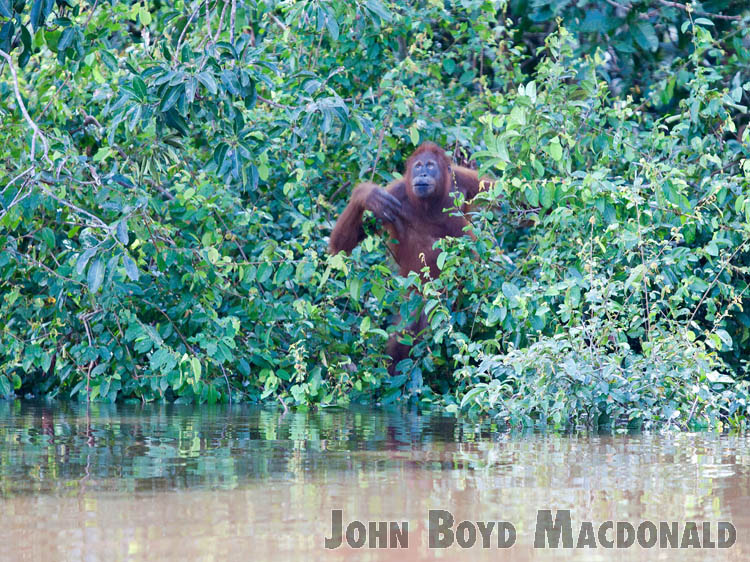

Orangutans will wade – but they do not swim. That’s why individuals being prepared for return to the ‘wild’ are held by the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation (BOSF) on three islands in the Rungan River (just a few km from our home). There’s no danger of them escaping from the islands.

They eat fruit – lots of fruit, comprising around three-quarters of their diet. They will also eat some young leaves, shoots, bark, insects and ants, honey and birds eggs.

Apart from mothers and their babies, orangutans tend to be fairly solitary – more so than gorillas or chimpanzees.

Babies stay with their mothers until at least the age of seven, and sometimes into their teenage years.

In the wild females won’t become pregnant until their previous baby is at least seven years old. This is the longest inter-birth period of any primate.

They sleep at night in a nest made high in a tree from bent and interwoven branches and a mattress of leaves. Usually a new nest is made each night. Nest-making is a learnt skill, usually learnt from the mothers by the age of three. The orphaned orangutans at BOSF go to ‘Forest School’ where they learn nest-making from their human teachers.

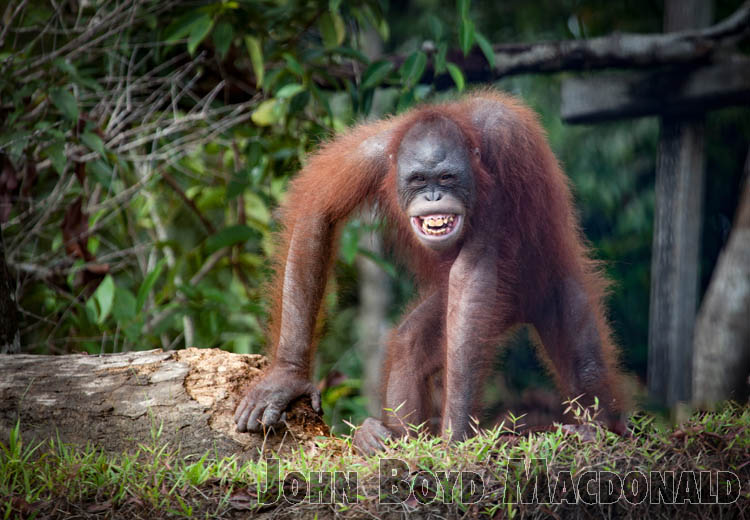

When angered, an orangutan will suck in air through its pursed lips, making the ‘kiss squeak’ sound.

Rescue, rehabilitation and re-release of orphaned orangutans is both worthy and worthwhile – but it’s not going to be nearly enough to counter the rapid decline of the populations due to loss of forest habitat.

As the ecologist Dr Erik Meijaard, from Borneo Futures, has observed: “The balance in orangutan conservation is not right. In the past decade we lost some 25,000 wild orangutans and we rehabilitated a few hundred. Very few are investing in on-the-ground orangutan conservation. It’s like fighting a war with hospitals and nurses only.”

Extinction in the wild within a generation remains an appalling possibility.