George Augustus Robinson travelled across the Monaro in 1844, in the course of his duties as ‘Chief Protector of Aborigines’ for the Port Phillip District. The journal that he kept during that journey provides some great insights into the lives of the early European settlers , the Ngarigo people whose land they ‘settled on’, and the attitudes of the time.

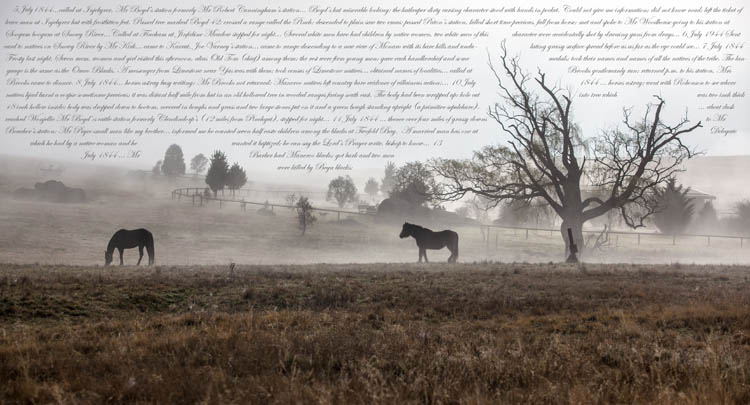

In the extracts incorporated in this image, he wrote:

5 July1844…called at Injebyrer, Mr Boyd’s station formerly Mr Robert Cunningham’s station… Boyd’s hut miserable looking; the hutkeeper dirty cursing character stood with hands in pocket. Could not give me information; did not know road; left the ticket of leave man at Injebyrer hut with frostbitten feet. Passed tree marked Boyd 42; crossed a range called the Pinch; descended to plain saw two emus; passed Paton’s station, killed short time previous, fall from horse; met and spoke to Mr Woodhouse going to his station at Soogum boogum at Snowy River…Called at Fincham at Jindabine Meadow stopped for night… Several white men have had children by native women, two white men of this character were accidentally shot by drawing guns from drays…

6 July 1944 Sent card to natives on Snowy River by Mr Kirk… came to Karrut, Joe Varney’s station… came to range descending to a new view of Monaro with its bare hills and undulating grassy surface spread before us as far as the eye could see…

7 July 1844 Frosty last night. Seven men, women and girl visited this afternoon, alias Old Tom (chief) among them; the rest were firm young men; gave each handkerchief and some medals; took their names and names of all the natives of the tribe. The language is the same as the Omeo Blacks. A messenger from Limestone near Yas was with them; took census of Limestone natives… obtained names of localities… called at Brooks gentlemanly run; returned p.m. to his station, Mrs Brooks came to dinner.

8 July 1844… horses astray busy writing; Mr Brooks not returned; Maneroo natives left country bare evidence of villainous action;… 10 July 1844 … horses astray; went with Robinson to see where natives had burnt a corpse sometime previous; it was distant half mile from hut in an old hollowed tree in wooded ranges facing south east. The body had been wrapped up; hole cut into tree which was two inch thick 18 inch hollow inside; body was dropped down to bottom, covered in boughs and grass and two large stones put on it and a green bough standing upright (a primitive sepulchre). … about dusk reached Wonjellic Mr Boyd’s cattle station formerly Clendindorp’s (12 miles from Pinchgut), stopped for night…

11 July 1844 … thence over four miles of grassy downs to Mr Boucher’s station; Mr Pryce small man like my brother… informed me he counted seven half caste children among the blacks at Twofold Bay. A married man has one at Delegate which he had by a native woman and he wanted it baptized; he can say the Lord’s Prayer write, bishop to know… 13 July 1844 … Mr Barber had Maneroo blacks; got bark and two men were killed by Bega blacks; Maneroo blacks killed two men Queenbeers sometime ago so Mr Robinson…

He base image was take as the dawn fog was lifting on the outskirts of Dalgety.