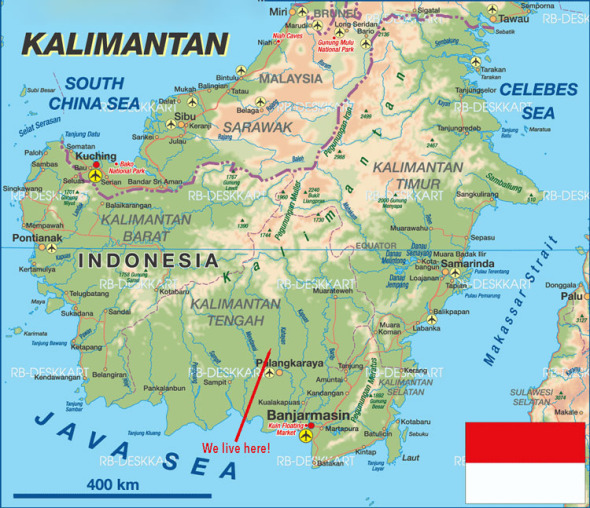

The dry season has begun here, and the smoke has started to thicken from the countless fires across the island of Borneo (especially our part of it…!). Soon it’ll be mask-wearing time again. The smoke is likely to worsen from now until the wet season starts some time around November – though the forecasts for a doozy El Niño event suggest that this year’s rains may be delayed into 2016. Everyone looks forward to the arrival of the rain.

And the wet season is also keenly anticipated because it is … Durian Season! This fabulous odorous fruit is available here from December through to February. Regarded here as raja buah (the ‘king of fruits’), the segments of this 1-3kg fruit segments have custard-like flesh around the seeds (which are also edible). It’s delicious, and quite unlike any other fruit that we’ve tasted.

It also smells a bit – well, a lot actually – even before the fruit is opened, and we often see signs at hotels and public transportation advising that possession of durian is prohibited. We like the smell (in moderation), though some people consider it repulsive. Having spent a couple of hours travelling a car with the back section stacked up with fresh durian fruit, we can confirm that the scent can be a little overpowering.

There is an Indonesian saying: Durian jatuh, sarong naik (“The durian falls and the sarong rises”), referring to the supposed aphrodisiacal qualities of the fruit, but we can’t directly confirm this to be true.

There are a number of different species of durian, at least nine of which are edible, and a large number of cultivars. They are all members of the Durio genus. The trees grow large, up to 25-50 metres depending on the species. They all have thick hard skins (to survive falling from the trees when ripe), which are adorned with hard sharp spikes. In fact the word duri means ‘spike’ or ‘thorn’ in Indonesian (and Malay).

Durian from the Katingan River region to the north of Kasongan, about an hour to the west of where we live, are prized for their flavour, and are priced accordingly.

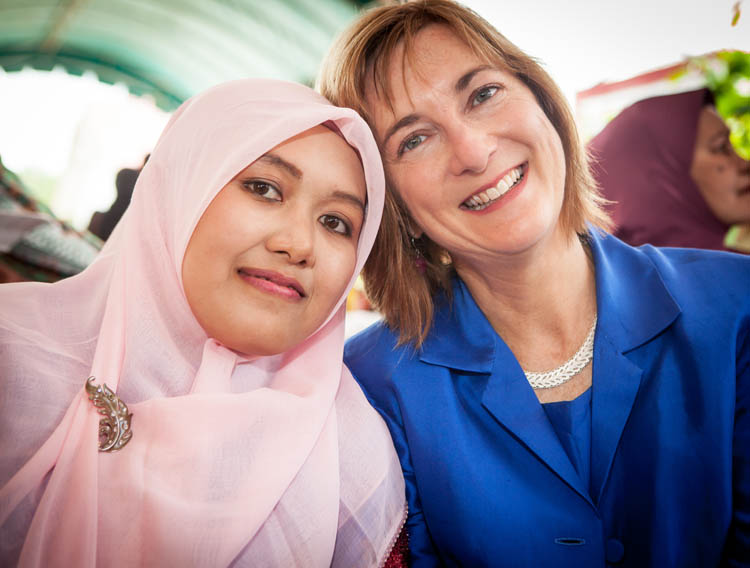

The village of Tewang Rangkang, which we have now visited several times with our friend Lelie, is right in the heart of the Katingan durian-growing region. There are numbers of the big trees in plots on the outskirts of the village, each plot belonging to a local family. In each one there is a simple wood-and-tin shack/shelter (pondok). Throughout the fruit season, family members take turns to sleep overnight in the pondoks, to guard against thieves making off with the valuable fruit.

The pondoks may be simple constructions, but they always have a strong roof. A heavy durian falling from 40 meters onto your head could be fatal… (even worse than a coconut!)

Durian trees flower in September – October, and the fruit are collected as they fall from the trees around three months later. The flowers of most Durian species are pollinated by bats.

The ripe fruit fall to the ground with a bit of a whoosh and then a big thump when they land, making it easy to locate each new incoming Durian missile. While we were visiting, everyone made a game of racing to be first to get to the newly descended fruit.

With Lelie and her sister Susi we dropped in to visit at a neighbouring pondok. Ibu was preparing a meal of forest mushrooms, which she kindly shared with us. In her batik blouse, bathtowel cummerbund and leopard-skin tights, she displays a fashion sensibility of refreshing individuality. The mushrooms were delicious.

Attached to the outside of the pondok was a web with perhaps the biggest spider I have seen. I didn’t get close enough to measure it, but I estimate it to have been easily 20cm across. Those long spidery legs looked strong enough to pick up durian…

Back at Lelie’s family pondok, a barbecue was under way. Fish caught in the Katingan River (some fresh, some dried and salted), local free range chicken (ayam kampung), and rice and veggies from the family’s ladang gardens. I think that the only purchased ingredient was salt.

Tante (Lelie’s aunt) likes a good joke and a bit of teasing, and so she made an elaborate show of not wanting to share the barbecued food with anyone. Fortunately she wasn’t serious…

And so we tucked in. The sambal was mostly garlic, tiny onions and chili, crushed on the flat hardwood mortar (cobek) in the picture above. Karen enquired about the wooden cobek, which had been made by Uncle Itiu. He slipped away after lunch and came back with a gift for Karen – a ‘spare’ cobek that he had at home…

After lunch, Lelie, Karen and Enjel found a shady spot to relax – but it was NOT under a Durian tree.

And Enjel borrowed her mum’s fan to keep cool – or to play with.

As the day went on, the stockpile of Durian fruit grew larger and larger. And that’s how we came to be travelling in a car loaded up with fuming Durian when we returned home that evening.